One of the great tragedies of human nature is that many of our greatest advancements come from our greatest conflicts. Nuclear power, radar, the internet, the list goes on for inventions that were born of the necessity of war. One often overlooked aspect of the advancements that come from war is the huge transformation in surgery that it has brought.

Emergency medicine was born on battlefields and many modern techniques were developed during conflicts around the world. It is a sad fact that the reason facial reconstruction surgery was invented was to help people who had their faces torn to pieces by bullets, explosives, and shrapnel, not because of the concern for people who were born with facial disfigurements or had accidents.

World War I

Although reconstructive surgery goes back to at least 800 BC, the birth of modern reconstructive and plastic surgery took place in what was called the “war to end all wars”. As the powerful nations of Europe each slaughtered young men on the battlefields of Europe, Asia and Africa, modern surgical techniques meant that many previously unsurvivable injuries were now survivable. Increasingly efficient methods of killing and maiming, combined with the sheer volume of young men who were returning from the front with life-changing injuries, meant the public had to stand up do something about it. It was no longer possible to hide away disfigured people when they were everywhere and they were heroes.

Shrapnel from shells had transformed an entire generation. Everyone had mental scars from that conflict but some had survived terrible bodily injuries. Very often they had had their facial injuries stitched up quickly and by surgeons without the requisite skills. As their scars healed, their skin stretched over their faces and formed horrifying visages. Gaping holes where eyes had been, missing cheekbones and jaws, holes where the nose used to be, these young men were no longer those outwardly recognisable boys they had once been. They often came home to discrimination, disgust, and few prospects.

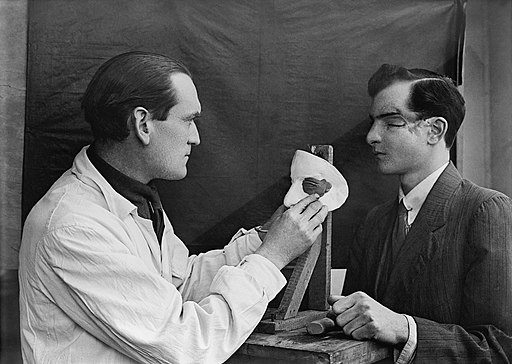

The birth of plastic surgery can be accredited to largely the work of one man. Harold Gillies, a surgeon from New Zealand who had trained in England and served in France in 1915, witnessing first-hand the terrifying rise of facial wounds from that conflict. He came back to England and set up a dedicated ward for the treatment of facial wounds at the Cambridge military hospital in Aldershot. Within a year his ward been so successful that he had managed to persuade the medical chiefs to set up specialist facial injuries units.

Pioneering work on skin grafts and reconstruction of facial structures took place during this time. Large skin grafts had never been successfully attempted before, but Gillies and his team managed to secure the blood supply to the new tissue that allowed it to live. It was not possible to restore somebody’s face who had been almost destroyed, but it was possible to give them a semblance of humanity. Needless to say, there was massive demand for it.

Between the two world wars, the techniques and expertise spread around the world and were advanced considerably. However, it was World War II that saw the next great advancements in facial disfigurement surgery.

World War II

By the late 1930s, surgical techniques had improved so greatly that many more soldiers were surviving than even in WWI. The nature of the conflict had changed, however, and young men were killing each other from aeroplanes and tanks. The result of this new form of conflict was a huge rise in the number of large body burns. Pilots trapped in burning fuselages, tank crews cooking inside of their metal tombs. This time, it was the turn of Harold Gillies’ younger cousin, Archie McIndoe, to pioneer the next revolution in plastic surgery. He managed to save many young pilots lives and improve their lives with the aptly named Guinea Pig club. These were young men who had been so severely burned but they were unlikely to survive unless they received new forms of treatment. Essentially, they signed themselves up to be experimented on. McIndoe built on the plastic surgery techniques of his older cousin and many of these men survived. He was instrumental in raising awareness of their conditions and money for further surgeries and campaigns.

As the availability of penicillin meant that many more young men with surviving, and the infections from burns were no longer a death sentence, the number of people who are needing facial reconstruction surgery increased. The Guinea Pig club was essential in raising awareness of burns disfigurement. National campaigns created media attention and many modern plastic surgeons can trace they’re training and skills back to campaigns fought for by the Guinea Pig club. It is still going strong.

Even today, many of the best plastic surgeons are working for the military or have gained experience there. The use of IEDs in conflicts such as Afghanistan and Iraq have once again brought the issue of facial disfigurement from obscurity and into the national consciousness.